Written by NDA tutor Amy Payler-Carpenter

Wassily Kandinsky, Yellow Red Blue, 1925

Wassily Kandinsky, Yellow Red Blue, 1925

If you think about the Bauhaus, you probably think of some of their most famous professors and students, the likes of Wassily Kandinsky or Marcel Breuer. However, whilst celebrating 100 years since the founding of this famous art and design school, it is important to remember some of the female artists who made a name for themselves at a time when its founder, Walter Gropius, believed women to be ‘too strongly represented’. To address this, The Women’s Department of Textiles and Weaving was set up, with the aim of freeing up space in the main departments for more men. Some women did join this specialist department, and others managed to make a name for themselves alongside the male students.

Whatever their path, here are just a few of the women who deserve to be remembered.

Marianne Brandt

Not only was Marianne Brandt a student at the Bauhaus but between 1928 and 1929 she worked as the deputy head of The Metal Department. The metal workshops would have been heavily male-dominated, however after talking classes taught by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, she caught the eye of the painter who believed her to have a unique talent. This was a woman who could turn her hand to most things; she started with tea sets in the workshops before moving onto lighting design for mass production. Before leaving the Bauhaus with her Diploma, Brandt worked alongside Gropius at his architecture office, designing the interiors for the Karlsruhe-Dammerstock housing project after which she would go on to enjoy a long career designing and teaching, not only in Germany but worldwide.

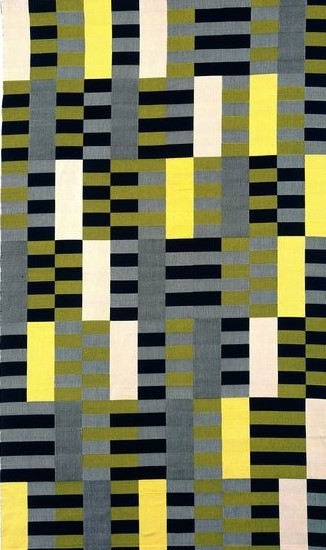

Anni Albers (1899 – 1994)

Anni Albers was actively discouraged from taking classes at The Bauhaus that the founding members believed to be male subjects. Gropius is even recorded as saying that 3D work, furniture design and architecture, for example, was too complicated for the female mind, which should stick to 2 dimensions. Thus, Albers joined the Textiles and Weaving Department. Like Brandt, Albers continued to work at The Bauhaus after she received her diploma in 1930. She held the position of the Head of Textiles and Weaving until 1933 when The Bauhaus was disbanded due to the rise of the Nazi party. At this point, she fled to America, and continued teaching. Her first major exhibition was held at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1949, and this would be the first of many showing not only her textile work but her later print work.

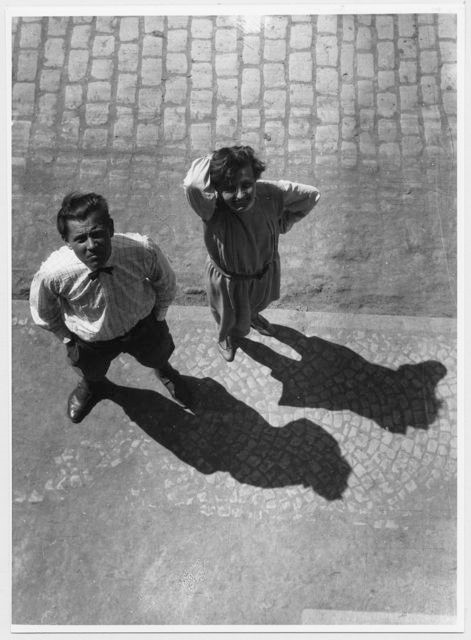

Gertrud Arndt (1903 – 2000)

Gertrud Arndt wanted to be an architect at a time when a woman’s opportunity to do so was still limited. She started to learn this trade as an apprentice in a firm, where she was charged with taking a camera on-site and taking detailed pictures of the buildings. In 1923, after seeing an exhibition of work produced by students of The Bauhaus, she enrolled with an aim to study architecture. However, at this time the course was not offered and would not be for another 2 years, so instead, she was encouraged to join The Textiles and Weaving Department. Arndt left The Bauhaus in 1927 with her diploma, never to work in textiles again, instead, she focused on another passion of hers, photography, with her main body of work consisting of self-portraits. She experienced little success in the early year of her career, but her images were revisited in the 1980s, becoming seminal to contemporary female photographers.

Margarete Heymann

Margarete Heymann is rarely considered when the great artists and designers of The Bauhaus are discussed. Like many of the women mentioned here, she was encouraged to join The Textiles and Weaving Textiles Department. Unlike the others, she refused. This refusal tainted her studies, with regular clashes with her ceramics teacher, Gerhard Marcks, resulting in her leaving the school only a year later. This did not dampen her passion for design and in 1923 she established a pottery firm with her husband. This was successful until the death of her husband, the economic depression and rise of the Nazi Party put a stop to her success, at which point she moved to Stoke-on-Trent, well known for its pottery. She would never quite regain her what she had lost, which may have been doomed from the start because of her gender.

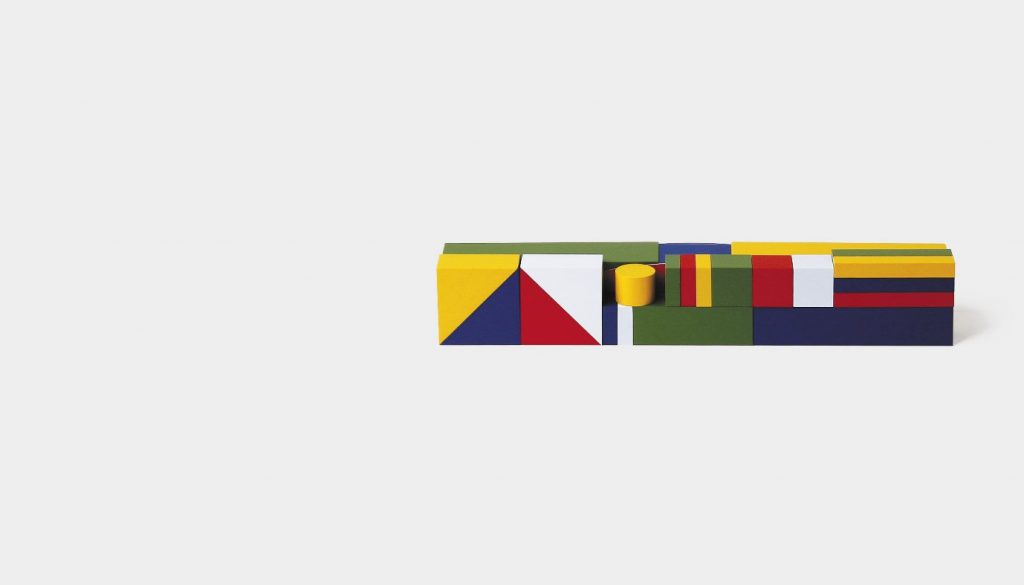

Alma Siedhoff-Buscher

Alma Siedhoff-Buscher started her education at the Elisabeth School for Women in Berlin, before joining the Bauhaus in 1922, and would continue studying there for 5 years. It will be no surprise to you by now to find out that she initially started in The Textiles and Weaving Department. However only months after joining her talents were spotted by Muche and Josef Hartwig at which point she switched to The Wood Department. Siedhoff-Buscher specialised in children’s toys, and among her designs was the Small Ship-Building Game, which contained building blocks that packed perfectly away into a small oblong box. This is still produced today and is as relevant now as it was then, regardless of changes in technology. Sadly, in 1944, she was killed during a bombing raid in Germany, but this would not stop her legacy living on in the toys she created.

The Bauhaus was a great institution, from which countless design icons emerged. Its attitude to women, by our standards, may seem out of line, however, the school was relatively progressive for the time as many other institutions would not have accepted women at all. We cannot change the treatment that some of these women suffered due to their gender, however, today we can remember them for their talent, and hold them in the same regard we would any of the males who came to represent The Bauhaus.